I have been talking about venture capital a lot recently.

A lot of my fellow MBA students are interested in getting into the industry so they are curious to hear my perspective on it. I also get frequently asked if I plan to return to the industry after I graduate. Anytime I find myself having the same conversation over and over again I have found it helpful to codify my thoughts in a blog post and so hopefully this can be a good resource to anyone interested in the industry as well as serving to get some of my feelings out of my head and into the open. Before we embark, I should say that this represents my personal thoughts and beliefs and could all be subject to change. I have spent a bit over 2-years working in the venture world and at least double that devouring everything I can about the space. My view is not ironclad, but I do feel strongly that my perspective is warranted and that it is my responsibility to share it.

I believe in Venture Capital

I believe in venture capital. I did three years ago when I was desperately working my ass off to try to find a way into the industry and I still do today. I believe that, when done right, venture is perhaps the greatest job in the world. You get to spend time supporting and working alongside entrepreneurs who are trying to change the world. It is extremely intellectually stimulating and it is an incredible job for anyone who loves to learn about new industries and technologies. When done right, it is one of the few true positive-sum professions where you only win when everyone else wins. When done right, incentives are aligned and I truly believe it is an example of a job where you can do well for yourself while also making a meaningful impact on the world.

Venture capital is great.

But it isn't perfect. And it's imperfections are exacerbated by structural and cultural issues that are pervasive within the industry. You'll notice when I was describing all the great parts of venture, there was a phrase I repeated a few times.

"When done right"

Therein lies the rub. Venture capital is an extremely compelling career path for a myriad of different reasons, but only when it is done right. What does it mean to "do venture right" and how does one do it wrong?

Venture done right

Doing venture the right way means optimizing for long-term incentive alignment between investors and entrepreneurs. It means focusing on maintaining relationships versus nickel and diming your way to a deal structure that optimizes for middling outcomes. Developing true conviction around the entrepreneurs you invest in and not simply throwing spaghetti at the wall to see what sticks. Venture done right is about paying it forward because you know that your associate or the VP at one of your portfolio companies could be a founder or co-investor in the future. It means getting in the trenches alongside founders and supporting them however is most helpful instead of touting the benefits of a promising-sounding, but inevitably spurious "platform" model. Venture done right is about evaluating people on the basis of their ideas, drive, and accomplishments and not because they pattern match to what a successful entrepreneur or investor looks like. It means being able to have tough conversations and maintaining respect for the entrepreneurial journey. It means not assuming you know all the answers and avoiding becoming cynical after the 10th time you've heard a similar pitch because that just might be the time it finally works out.

Notice there are no parameters around fund size or industry or geography. There are a lot of ways to be successful doing venture, but if you look towards the upper echelon of funds that consistently outperform the rest of the asset class, I believe you will see that the "how" they go about the job contains many of the aspects I outlined above even if their specific strategies and focus areas may differ.

To answer the questions I get about my post-graduate plans, I would absolutely go back into venture. But only if I had the opportunity to learn from a master of the craft at a firm that did venture the “right way.”

Unfortunately, I have come to believe that those kinds of opportunities in the industry are relatively few and far between.

Venture’s sexiness problem

So why don't more firms do venture the "right way"?

I think it is largely because VC has a sexiness problem. It is so attractive from the outside looking in that structural issues are created or allowed to fester. There are a massive amount of young, smart, driven people who are fiercely interested in breaking into the industry. And as I outlined above, I believe that is for good reason! Let’s look at why this causes some problems.

On the demand side, you have an overabundance of smart, driven people trying to get into the industry. On the supply side, you have funds that only hire based on fund cycles every few years and are generally top-heavy with more senior-level investors than mid-level investors and more mid-level investors than junior level investors. These combine to make it incredibly difficult to go straight into the industry. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing in and of itself. There are plenty of industries that are competitive. But a commonality between many of them is that they treat people like crap.

Look at fashion, sports, media, and investment banking. All have way more demand to get into the industry than supply. And they treat people (especially junior-level people) not especially well. Why? Because they can. Because if you don’t like it, there are plenty of people riding the bench who would be more than happy to take your place.

I am not saying that everyone in VC gets treated like crap. Quite the opposite in fact with the collaborative nature of the industry generally leading to a kind of friendly “coop-etition” between firms. But speaking from my personal experience, as well as those of my friends in the industry, there is a dearth of mentorship, advancement, and opportunity for growth. And that is allowed to occur systematically because there are so many people who want to get into the industry. There just isn’t an explicit reason to give up time and resources to nurture talent when there will always be someone waiting in the wings to take their place. I’d argue that there very much are long-term reasons to develop junior-level folks, but this is an industry where feedback loops are long and most firms aren’t trying to build a legacy.

The recent sheen of the venture capital world has some other unintended consequences. When an industry seems too good to be true it has a nasty habit of attracting snake oil salesmen. I think venture capital is especially susceptible to this given the industry’s long feedback loops and general opacity. From the outside looking in, it is hard to tell the good VCs from the bad ones. Their branding and social media presences look largely the same. They use the same buzzwords and both talk about their love of innovation and working with entrepreneurs. There is a scorecard in the form of returns (which I believe largely accrue to investors who do venture the right way), but you have to be an insider before you really get a sense of where the leaderboard stands. Sophisticated LPs and entrepreneurs can smell the difference a mile away, but many other investors, entrepreneurs, and corporations don’t have nearly as discerning of an eye. This isn’t just a coastal tech hub phenomenon either. Go to any up-and-coming tech ecosystem and you will find it run by old white guys who last worked at a “startup” when AOL came on a disk.

Should you go into VC?

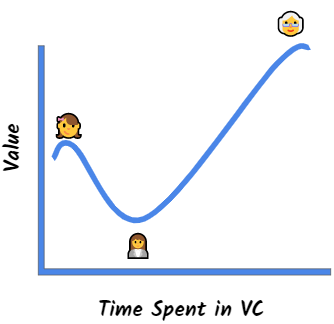

That depends. I am increasingly led to believe that, on average, venture is a good but not great junior-level job, a poor mid-level career, and a fantastic senior-level calling.

Let me explain what I mean by that. I think the value you will get from working in the venture industry follows a barbell and is a function of time spent in the industry.

On one hand, you have venture as a junior-level job. Like it was for me. The reason I got into venture was not because I wanted to do venture until the day that I died, but because I wanted to be part of building companies that make an impact by solving important problems. That's my north star and it is what guides every decision I make in my career. I thought venture would be an excellent introduction to the world of tech entrepreneurship especially given my background with finance and investing. The type of startup that I could've joined given my skillset a few years ago as a financial or business analyst would have been at a very different stage of maturity than the kind of startup I could be part of now. And I would have only had one perspective on how a company gets built instead of having at least somewhat of a view across the landscape. That was my thesis at the time and I think it largely came to fruition. I feel 1,000x more equipped to start or join an entrepreneurial endeavor than I was a couple of years ago. If you want an industry to go into for a couple of years where you can learn about a ton of different companies and sectors and get broad exposure to the technology industry, venture is a pretty sweet gig. In hindsight, I think I would have learned more by joining a successful startup during its hyper-growth phase, but finding a firm poised for that kind of growth is easier said than done and going the venture route was probably the next best thing.

Where the industry is challenged is from a mid-level career perspective. As mentioned above, opportunity for organic growth within firms is pretty tough to come by. You will see or meet people who are flying up the ladder at their firms, but that is because they belong to the minority of firms that do venture the “right way”. Who are willing to think long-term and know that developing talent in-house leads to long-term competitive advantages whether that talent stays, goes to another fund, or starts their own company. That means that this mindset is not pervasive in the majority of firms in the industry. It is a tough, tough climb to scale the venture capital ladder purely on the investor side of things. It can be done, but usually, it takes stops and starts and a decent amount of bouncing out to move up. Maybe my perspective is somewhat jaded, but from where I sat for two years, I’d say my experience was much more emblematic of other junior-level investors in the industry than not. There are better and much easier ways to make money and build a career than working in the venture capital industry. If that is your primary motivator, I think you will find yourself frustrated.

Where I think venture really shines is as a senior-level calling. I think being a GP or partner at a venture firm is probably one of the coolest professional pursuits in the world. If you truly view it as your life’s great work to support entrepreneurs and help enable them to build incredible business, boy is the payoff big. I think the investors who do venture capital the right way largely fall into this camp. They don’t do it for the financial rewards or the perceived pseudo-celebrity status. They do it because they are obsessed with the craft of building companies. Yes, venture capital is an asset class, but I believe it is, and will always be, much more art than science. It truly is an apprenticeship craft and if it is your life calling, becoming a master artisan is an incredibly compelling path.

What can be done?

So what can be done about these problems?

To would-be VCs: Be picky. Don’t settle for the first offer you are able to get. Really dig in and try to understand whether a firm does venture the right way. Do your due diligence on them just as you would if you were evaluating a company. You may think it is worth it to take any job just to get a toe hold in a competitive industry, but I can assure you it is better to bide your time for the right opportunity. If you are determined to make it as a VC the barriers ARE surmountable. What may not be is the damage done by going to the wrong kind of firm. As with any kind of apprenticeship, if you are learning the craft from practitioners who don’t do it the right way, then you are learning to read from the blind.

To founders: Be skeptical. Don’t sign your life away to the first term sheet you get. Venture capital is a long-term commitment and it is worth taking the extra time to do your due diligence on your investors. Talk to the references they provide you and then talk to the ones they don’t. Dig into the portfolio companies they cut ties with or who they didn’t follow on with. If you get a glowing review from an entrepreneur who a firm didn’t continue to invest in that is a strong endorsement indeed. Avoid incubators, studios, and accelerators who over promise and under deliver. There are firms in each category that are fantastic, but there are significantly more who don’t add nearly the amount of value necessary to justify the commitment (in time, equity, and energy). Be wary of anytime the public sector tries to start getting involved with directly funding or spurring innovation. It can be a recipe for misaligned incentives and bureaucratic optimization of all the wrong things.

Despite all of its issues, I still believe that venture capital holds incredible promise. Promise to really enable significant good in this world. In some ways, it shines so bright that it casts shadows, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t a massive net positive on our society. If after reading this, you still want to pursue venture capital, great! You should go for it with eyes wide open to all of its greatness as well as all of its failings. When you are a wildly successful VC, I hope you take the long-view and do it the right way.

Venture capital is not the best career in the world anymore.

But if people focus on doing it the right way, by optimizing for long-term incentive alignment and taking the long-term perspective on nurturing talent, I believe it can be once again.

If you have thoughts on this post leave a comment below or reach out to me on twitter @abergseyeview where my DMs will forever be open.

If you enjoyed this post, you can subscribe here to receive all of my posts delivered directly to your inbox every Monday morning (or the occasional Tuesday).

If this is the first time you are reading something I wrote and you want to learn more about me, this is a good place to start. It includes some background on me as well as a collection of my top posts.